- Home

- Daniel Arnold

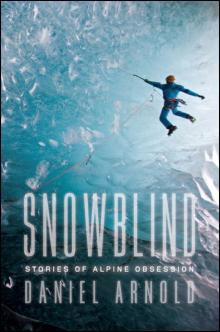

Snowblind Page 19

Snowblind Read online

Page 19

A stone thrummed through the air outside the groove, crashed off a snaggled horn, then gathered momentum again. Dane passed a nylon sling, barely held by a vein of rotted ice. Asa had been here. Dane gave the sling a controlled yank, and it ripped free. How much ice had there been? The mountain was shedding its skin. Everything he saw was temporary.

A hundred and fifty feet. No matter how unkillable Dane felt, he’d have to stop and belay, and he’d seen nothing so far but papery rock in overlapping leaves and scales. No cracks, nothing to anchor two human bodies in even the most illusory way. Dane looked around, looked up. Higher, he saw a mushroom blob wedged into the groove. A chockstone? A deeper lode of ice? Dane padded up toward it, the rock creaking, his crampons squeaking, reaching it just at the end of the rope.

Not ice. Not a wedged stone. Leo.

Wedged head down in the groove. Come to rest with his legs bent and splayed. Iced over and locked in. Rope ends trailed down into the groove. Dane levered experimentally on one of Leo’s stiff frozen legs. No movement, no shifting. In all of that frail rock and shattery ice, Leo was stuck fast, fixed to the mountain for however long it would hold him. Dane unclipped the anchor cord from his harness, wrapped it around Leo’s thighs, clipped himself in, leaned back, and yelled down to Asa to climb.

“Thanks, buddy,” Dane whispered, after a long moment. How much should he say to Leo’s body? Dane shifted his stance but saw how the cord bit into Leo and kept himself still. Brother? Miss you? Damn you? For falling up here and leaving us all more alone? It was so fucking futile, seeing how the mountain had smashed and half eaten him. On our earthly hell, the dirt eats us, one and all. Maybe you get a cross (or a leg) sticking out for a time to comfort your friends. Asa must have known Leo would be here. No wonder he looked drawn. And Dane yukking about ghosts. He was the goddamn creep show.

Asa came up from below. Dane leaned aside to let him see. Asa locked his crampons across the groove, stopped, shut his eyes, opened them, canted his head.

“You cocky son of a bitch,” Asa said to Dane, with a kind of soft wonderment. “You are going to get me in trouble.” Asa reached up with one axe and poked Leo in the hip.

Dane hadn’t intended any disrespect, turning Leo into a bollard. It had just happened. In fact, Dane sensed a rightness in being held to the mountain by Leo, though an upside-down Leo made the rightness grim. The world was grim, covered two miles deep in geologic piles of dead critters. Leo’s sum of pretty words didn’t change the nature of the dirt.

So to Asa, Dane said, “I wouldn’t worry. You’re nowhere near as dark as the universe.” The only protest Dane saw—the one thing that didn’t follow the deterministic biological imperatives to get fat and multiply, to spread more little deaths far and wide—was to go right at the darkness, find its scariest earthly representatives, and attack them. The futility itself, the rank illogic, was its own escape.

Asa took back his axe and said, “I’m cheerful fucking company compared to the universe.” Dane had to lean in to hear, Asa spoke so low: “It had been a good, fast day. We were in a lull, like now, the sun was out.” He’s had no one to tell this to, Dane realized, and he thought of a confessional, a sick thought, with no one to hear it but himself and Ozdon. “He was sixty feet up, and he yelled down he wanted to go look at that rock up there.” Asa pointed to a gigantic corkscrew tusk of mottled stone. That was Leo, wandering off to see things. He must have been desperate—the spire was cock-ugly, Satan with syphilis, and the traverse out of the groove climbed detached shingles that looked hung by force of habit only. “I told him not to go up there. I told him not to fall. Then the rock clapped, and the rope went slack, and I thought we were both dead for sure. He went in headfirst. Like the coyote, like a fucking cartoon. I cut the ropes and rapped off a sling in the ice.” Asa looked at Dane as if he’d just remembered Dane was there. “We need to move. It’s haunted here. And you’re no help.”

Asa took the gear, put a hand on Leo and whispered something Dane couldn’t catch, then he climbed past and was gone.

Dane didn’t mind having another moment alone with Leo. He caught Leo up on small things. After all the winter snow, the flax and columbine had been outrageous in the spring. There was a woman he had a thing for back at one of the labs, a runner, and with her lab coat and corn silk ponytail, he thought Leo would approve. Driving through thunderstorms in the desert on a full-moon night, he’d seen a midnight rainbow like an oil slick in the sky. A lot stores up in a man over half a year. Dane noticed that one of Leo’s legs bent the wrong way. The force of the fall, or maybe debris flushing through the groove. And Dane thought: what’s more horrifying than the mind’s ability to adapt itself to horror? Asa’s voice fell down to him out of the hard blue sky. The rope went tight, and Dane climbed, leaving Leo below.

Dane’s thoughts wandered back to the Wasatch, where it all began so casually. No plans, no purpose, just two kids and the mountains. On Ozdon, he hooked the wrong flake and popped off a plaque like a saw blade, which smoked through empty air while Dane caught himself on one tool. Mountain and mind were each full of traps. The groove disappeared under a stack of overhangs. Asa led out through cracks bleeding clear ice. Dane dry-tooled a vertical wall of quarter-inch edges, working to keep his brain in a narrow tube, only one direction to see. A flight of hail rattled by. Wind gusts pounced.

The weather closed back in. Heavy clouds dumped snow into a banshee wind. Perched side by side on a crumbling shelf of rock, Dane and Asa each wrapped an arm around the other’s shoulder and huddled their heads.

“Can’t climb,” Asa shouted. “Might as well sleep.”

“Hope we wake up,” Dane said.

“Just listen for the yelling,” Asa said. “I never sleep long. Too much can go wrong.”

Dane wrapped himself in his bivy sack and sleeping bag, allowing about a bushel of snowflakes to press in before he sealed out the world. He curled up on the ledge, a tight umbilical connecting him to the anchor. Through his nylon skin, Dane felt the wind all around him, the snow outside and in. Gravity fingered the parts of him that hung over the edge. Asa, in his own cocoon, wedged against Dane to share the fattest part of the ledge. Leo leaned against him on the other side. Dane closed his eyes anyway and fell down a dark shaft of sleep.

Dane woke with a pillow pressed over his face. No. Snowfall. He pushed away the fabric of his bivy sack and felt a pile of snow slough off. The cold had invaded. His feet were frozen blocks. The wind had dropped to a background pulse. And Asa was screaming. Dane could only make out a word in three, but he caught the gist. Asa was cursing Ozdon, taunting it.

For the first time, Dane considered what it would do to a man to climb only this one mountain, where there was nothing to love, no break from the rituals of combat. Nothing pretty to make the eyes glad. And if he feared sleep? Could Asa sleep in winter, when it was night only, and the rest of northern humanity hibernated like bears? Or did he stay awake then too, in his shop, knowing the mountain was out there waiting for him in the dark?

Dane unzipped the hood of his bivy sack. Windblown ice scraped by him, but the worst of the storm was past. Asa was sitting upright on the ledge, wrapped in his sleeping gear, still yelling. “Asa,” Dane said, “don’t you ever leave Fort Clyde?”

Asa quit his tirade. The cowl of his sleeping bag turned Dane’s way. “You’re awake. I was starting to wonder. Been years. I know my place.”

“You don’t have to marry her. You can climb other mountains.”

“Fuck you. I’m trying to kill it, not marry it.”

Leo bubbled back up in Dane’s head: “Leo would think you’re just trying to kill off something inside yourself.”

“He and I agreed on that.”

“And that’s fine with you? Most people enjoy climbing.”

“Thrill seekers and hypocrites. They want a little taste of death, just enough to get their juices flowing. Then they run back home and puff up around their friends. A little spoonful of death right in

the vein for fun on the weekend. Soulless motherfuckers make me want to puke.”

“Leo was trying to help you, wasn’t he?” Dane said to Asa. He was still trying to justify Leo’s presence on the mountain in his own mind. “He thought he could make you see different.” Dane looked around for an example, a piece of the mountain Leo would point to and make one of his poeticisms. Something better than a twisted devil dick. No luck. Dane felt like a fly staring up at a spider.

Asa laughed and squeezed Dane’s shoulder with one gloved hand, giving it a shake. “Our boy Leo had horns and fangs. And he didn’t know what to do with ’em. Didn’t fit his image at all.” Asa unzipped his sleeping gear, tightened himself to the anchor, emptied his pee bottle. “I’m doing the world a favor. I could be bombing people’s countries or shooting their sons. People been doing that for all time, trying to kill off their own demons. I’ve got my corner of the world, and I stay put. Fight for the territory inside. I’m goddamn civilized.”

Dane tried and failed to grow horns on Leo. They wouldn’t take. All he could see were two legs sticking out of the rock—Leo kept slipping away until Dane couldn’t even trust that image of him grinning in the sun and porcelain snow. Was it from a mountain they’d shared? A book jacket? Dane flexed blood into his toes and slapped the rock with his hands because they felt like plastic and it was his lead.

Powder snow on black ice, hard as concrete. Guillotine flakes of rock, shifting and creaking. Dane watched a hundred-pound scab slough loose and chop the rope, the anchor, Asa, then had to wake himself to the reality that he was still holding the flake’s edge, feeling the rock grind. The wind razored past the mountain, and when it hailed, Dane felt the ice shiv into his brain.

Delusions and terrors crowded Dane’s mind. He kept seeing what the mountain could do to them. The images were so close to the surface he stopped trying to defuse them. He hunkered down away from his imagination, from the future, from any thoughts past stabbing the mountain and pulling his corpse higher.

At the belays, they traded gear in silence, a pair of hooded monks executing rituals that already felt old as the mountain. They’d stopped needing words with each other. The rope swap happened automatically. When Asa was climbing, Dane could all but see out of Asa’s eyes. And when the rope was stretched out between them at the end of a pitch, they couldn’t have dented the wind with megaphones, so they spoke through the movement of the cord that bound them.

At first Dane had resisted the connection to Asa because Asa was such a malignant motherfucker and Dane wanted no comingling of their minds. But the truth was, Dane knew what was going through Asa’s head just by the way the rope twitched. Pretending otherwise was pointless.

The storm shredded them. Dane could hardly believe there was anything left of the mountain, that it hadn’t been worn to a stub by the weather. The wind was alive, bloodthirsty. It jumped down Dane’s throat, tried to turn him inside out.

Dane lost his grip on where they were or what they were doing. There was one direction: up. One way to pull, one way to fall. Time quit moving forward—it only cycled between the ebb and flow of the storm.

The mountain stopped. Dane didn’t know what to do. He almost fell over. The summit was an island of vertigo in the wind, nothing but dirty air circling a spike-head of stone. They spent all of ten seconds on top, the time it took Asa to rig their first rappel.

They slid down their ropes, undoing what they’d done. Down and down. Falling snow turned day into twilight, the wind still smacked them around, but gravity had come round in their favor. They down-climbed anything they could solo and rappelled the rest. Asa knew the route down so well there was nothing for Dane to do but string along and let his mind out to wander. They followed snow couloirs, perfect avalanche hatcheries. Dane could hear the layers squeak under his boots. But they bombed down them anyway because it was fast, and they were heroes returning, invincible.

Consciousness—of the larger worlds outside and in—refilled Dane as he descended. The lower he dropped, the less ghostly he felt, the more full of life. Tired, sure, stumbling and dragging, making bad decisions and grousing jokes about dying like putzes on the descent. But also keen, farseeing. By the time they reached the ground and lay down on flat earth out of reach of the mountain, where Ozdon couldn’t kill them, Dane felt fully awake for the first time since setting foot in Fort Clyde.

Dane stared up at grey clouds, his legs twitching and cramping, his arms like wet clay. He had gone to the mountain to tend Leo’s body, and Leo remained there without so much as a cairn to mark him. Dane was pretty sure he hadn’t even adequately cared for Leo in his own mind. Leo would have claimed he never wanted to mark any mountain, but Dane didn’t know if he believed the man’s claims, and anyway, it was bad for his own state of mind to leave Leo festering up there.

He and Asa hauled themselves upright and began the long tundra slog to Fort Clyde. The only hurry was to end the physical misery of their bodies. Food. Drink. Chairs. Behind them, the mountain shrouded itself in clouds and a pyrotechnic lightning storm. Rain slashed down over the tundra.

“Just be glad we didn’t get caught in that,” Asa said, after a thunderclap that rattled Dane’s eyes.

“We should do something for Leo,” Dane said, rain streaming off his Gore-Tex. “Go back up and make him a monument or something.”

“Sure,” Asa said, looking bemused, “we should go back up there.”

When they staggered into town, they went straight to Baxter’s, the name of the flesh giant tending bar. They ate elk sausage. They lined up shots of the cheap whisky. Rain rattled the roof. Two other men griped back and forth with Baxter and watched the climbers.

“Like we’re zoo monkeys,” Dane muttered.

“They know about Leo,” Asa said.

Dane and Asa clinked glasses, drank. Dane gave the mountain the finger—there weren’t any windows at Baxter’s, but he and Asa both knew which direction the mountain stood, and Asa chortled. Dane cocked his arm round until his finger was jabbed at the men at the bar. They were square-fisted, red-faced hulks, insulated against the north with their own meat, and Dane saw in their eyes the calculation each made—that punching Dane would be like popping some skinny, strung-out addict, not worth a busted knuckle or a blood disease, and they turned back to Baxter. In his own outstretched hand, Dane saw the twisted claw of Ozdon, and he put it back down on the table. He and Asa hunched over their drinks, touched glasses again.

“To Leo,” Dane said.

“To Leo.”

“He should have stayed away,” Dane said. “I wish he had. He had no business up there.”

“He should have left it for sick fucks like you and me,” Asa said.

“But he didn’t. He came back.”

“That’s right. I told you, climbers come here. Can’t help themselves. Like flies to meat.” Asa threw his last glass against the wall keeping Ozdon out of the room, and Baxter threw them out into the rain.

COWARDS RUN

HERE’S WHAT A seventeen-year-old will do: he’ll come into class one day with a leather jacket or a moustache or the key to a ’78 Power Wagon on its second engine and act like he’s scratching the world’s balls. For Skim, it was the day after he acquired his uncle’s boat, a nineteen-foot sloop named Coward’s Run. “First thing I did,” Skim drawled out from a tipped-back chair in zero period, an octave lower and twice as slow as I’d ever heard him talk before, “was paint out that damned apostrophe.” I’d never heard him concern himself with punctuation. What next? I braced for poetry. He had a dangerous look to him.

Now, “sloop” might sound handsome to you. It did to me, until I hunted up Simpson’s Nautical in the Gustavus public library and found out that a hog trough with a single mast through its middle and two sails would qualify, and that’s about what it looked like Skim’s uncle had given him. But Skim was ready to navigate the high seas. He wanted to smuggle in bales of weed from British Columbia or invade North Korea and bring justice to the c

ommies. He bragged about the boat’s—his boat’s—shallow draft and lift-up centerboard. He could land it on a beach in the middle of the night and no one would be a gnat’s fart wiser.

Wasn’t I seventeen, too? I listened to him rhapsodize about beach landings while we hunted and pecked through keyboard drills, then interrupted to ask the question which had been burning my mind for at least ten minutes: “Yo, Skim, why don’t we sail north, land your cockleshell in Lituya Bay, and climb Mount Fairweather from tidewater?” I watched his wheels spin like a four-wheeler in mud month—then he got traction, and we talked about nothing else till summer.

We grew up four houses apart on the old Strawberry Point, at the mouth of Glacier Bay. Skim’s dad taught him fishing and sea ballads; my parents gave me geology and Homer. We got on well with each other and our place in the world. Two hundred years ago, the present-day glaciers were all tributaries, and the Bay was the trunk of a honkin’ ice river. Strawberry Point was nothing more than the outflow plain of sand and gravel where the big glacier crapped out all the crushed-up mountain it had digested. When the big glacier absconded to join the mastodons and brontosaurs, the ocean filled in, and Strawberry Point became beachfront. To the south, we had waves and whales and cruise ships, the latter sliding by like alien rockets with no time for the natives. To the north was rain, snow, and mountains. Skim and I, we headed north when we could. We’d just walk out of town with our backpacks on, step into the woods, go uphill till we hit snow and ridgelines and summits.

The school and library were sidelong to the airstrip, and in summers, guys with carefully packed North Face duffels would land, hire ski-planes, and fly off to Fairweather or Mount Crillon. So we knew that there were bigger mountains around us, the kind that people from other states and countries would travel around the world to climb. But buying time in a ski-plane was a luxury beyond us. Money slipped by on the cruise ships, like seeing Los Angeles on TV. Folks in town went out to work the water, catching fish or tourist dollars as they could, but we were a stagnant little eddy outside the global currents. Besides, as I said to Skim one day on a practice run in the Icy Strait while we were disentangling the mainsheet in a rain squall that was about one degree too warm to be a blizzard, a ski-plane is a damned inelegant thing. Once you flew a plane to a mountain, what kept you from landing higher? Why not land a hundred feet below the summit? But a boat! No boat would float you higher than sea level.

Snowblind

Snowblind