- Home

- Daniel Arnold

Snowblind Page 18

Snowblind Read online

Page 18

“You know where Leo is?” Dane asked.

“Sure.”

“You’d take me to him?” It was a nightmare: Leo’s death, the mountain. Actually seeing Leo and tending his body seemed like the one thing Dane could do. Dane turned back around, taking a half-conscious step to the left so that his back was to the wall, not the window.

“I’ll take you to the body if you’ll climb the mountain with me,” Asa said. He grinned, all teeth and jutting bones. “Partners out this way are kind of scarce.”

“I’m not in the mood,” Dane said.

“Do you need to consult your chi? Do a little yoga?” Asa took his hood back off its peg. “Go drink some tea or whatever. Then we’ll talk.”

“You’re heartless, you know that? My buddy’s dead up there.”

“Yeah? Mine too. And I’m pissed about it. Been pissed off for two weeks. The mountain’s been laughing in my head.”

Is that what that sound is?

“You’ve been looking at it,” Asa said. “I saw you. If you think Leo wants us to hug and light candles, you can run on back to your lower-forty-eight commune. Or we can do something great for him. Strip our souls. Have our own little exorcism. Just don’t waste my time because I fucking hate indecision.”

Could Dane come right out and admit he was already hooked, that he’d been wanting to climb the mountain since the pilot first invoked it? No. “Fine,” he said. The roaring in his ears cranked up a notch.

Asa opened a cabinet in the corner of the shop. Dane looked over Asa’s shoulder at a compact arsenal of alpine gear: ice tools, crampons, ropes. The picks of Asa’s tools were beautifully resharpened—Dane suddenly saw Asa, the craftsman, hunched over his axes, grinding life back into his steel. Asa had sewn hard plastic scales to the outsides of the gloves hanging in the cabinet. Dane took one off its hook, put it on his hand, watched how the scales flexed and overlapped like a medieval gauntlet.

Asa grinned again, just teeth and no humor. “The inside armor’s what matters,” he said. “Put on what you’ve got.”

“When do we go?” Dane asked.

“Sun’s out,” Asa said. He clapped Dane on the shoulder. “No time like now.”

Dane wanted to say he hadn’t slept, that he was a dead man walking, but he didn’t care to weather more of Asa’s scorn, and he couldn’t see the point. He was dead on his feet, but he felt as remote from sleep as he did from reality. That bright sun! And the mountain was right there, even when he shut his eyes. And Leo was up there, somewhere, and Dane needed to find him, to ask Leo what the hell he was doing here.

Dane unpacked his gear from his duffle, and then they were out on the tundra with the brilliant midnight air running past them like a river and the mountain tearing into the sky. In his pack, Dane carried ice tools and crampons, one twin rope and half the rack, sleeping bag and pad, food for three hungry days. The closeness of the mountain was partly an illusion of its size. By the time the two men covered the miles from Fort Clyde, Ozdon had spread its wings, a black vulture nine thousand feet high.

On the tundra, Dane seemed to be following a wraith. Asa glided over the man-trapped ground, while Dane grunted and snorted twenty feet behind with the needle in the red. When he had enough breath, Dane caught hold of the questions swooping through his head.

“How did Leo find this place?”

“I found it,” Asa said. “And then I found Leo. I read a book of his and thought, there’s a rose-tinted douche bag who talks like an angel but thinks mountains are art or sun-children or some such bullshit. I sent him a picture of Ozdon and told him to come climb it with me and then call it beautiful. Called him out. He was a name on a book. I never thought he’d read what I wrote. I was pissed off, firing shots in the dark one night. Tired of people going out like they’re collecting flowers and calling it climbing.”

“But he came,” Dane said. He could imagine the photograph worming into Leo’s brain. Leo would have to see it himself, make it fit into his world. A mountain that shouldn’t exist, but there it was.

“He came,” Asa said. “Three years ago. Tall brown stick of a dude, up north to convert the infidel. Insufferable bastard. I wanted to strangle him.”

The idea that Leo had traveled to Fort Clyde because of a photograph and some barbed words didn’t surprise Dane. Leo had followed leads more slender into the mountains. Dane didn’t understand why Leo had returned. Everything about the place—the concrete pillboxes, the mines, the fat pink hermit crab in the bar—ran foul of Leo’s carefully tended Zen-garden inner world. And above all, the mountain, snarling and foaming at the mouth—Dane watched as an avalanche galloped off the mountain’s shoulder, just to mark his thought. Who’d want to get bit by the same rabid dog twice?

“And he came back,” Dane said.

“Half a dozen times since then. I told you he was here. It got to be I could sense him coming before I even heard the plane.”

Dane didn’t say it, but that was more times than he had seen Leo over the same period.

The land scarred up where the mountain burst out of the tundra, and Dane quit talking to save breath. He followed Asa through snowfields and over steep, broken ground. Above them, the mountain revealed new faces, an ugly, death-row lineup. Fresh snow bearded the rock. Icicles—they must have been big as trees—fell through space and shattered against buttresses, popping distant explosions on impact. Snaggle-toothed towers rooted in gums of dark old ice broke through the faces and ridgelines. Despite the sun, the cold licked at Dane like it was tasting to see if he was good to eat.

A second wave of tiredness swamped Dane. He felt mired in place, barely able to move. Asa agreed to nap until the sun crossed out of the east—the ice would be firmer if they climbed with the sun in the west. Dane unrolled his sleeping bag without a word and stretched himself out under the blank sky and leering mountain, but though he had been all but unconscious on his feet, he couldn’t sleep. Now he thought of Leo, and Leo’s absence stabbed him no matter which way he turned.

Dane felt inadequate to the job of mourning. He should be wearing black, brooding, walking in the rain while his fellow sufferers thought, ah, there’s a man radioactive with loss. Instead he was climbing a mountain. Again. Which is what he did. The very mountain that had killed Leo. Did that make a difference? Leo’s haunt would be up there. Which was terrifying—Dane felt his stomach drop at the thought of his hands on the last of Leo’s holds—but so much better than an empty box and empty church. And the mountain, the slavering beast? He wanted to kill it! Ride up with gauntlets on his hands and put an axe in its neck. Leo would shake his head. What would he say, that Dane only wanted to kill the terror, the reflection inside? And did Leo have that much terror stockpiled that he needed to come back six times?

Dane had not realized how often Leo was in his head, had never told Leo, as far as he could remember, how much he looked forward to Leo’s return. Leo was like a second moon, familiar and strange, visiting him from distant places. When Leo told him about the Karakorum, Dane felt like he’d been there, as if Leo had carried along a piece of him. Dead, Leo was a phantom limb Dane couldn’t touch.

“At least he was doing something he loved,” Dane said, half-heartedly, eyes closed.

“Wash your mouth,” Asa said. “Best use lye.”

“I know,” Dane said, after a moment to study the platitude. “It’s like people will sell out their friends for comfort, just to dilute the pain. Make themselves feel better.” Then he fell asleep.

When Dane woke, the sky was a hairy underbelly of grey and black clouds. “So much for our weather window,” he said.

Asa was awake. Dane wondered if the man had slept, if he ever did sleep. Maybe Asa was one of the ones who’d gone crazy with the light.

“They never stick,” Asa said. “The next storm is always coming.”

The clouds pressed down, and the mountain disappeared, standing just behind the curtain, at the edge of perception. Each time Dane blinked, he thought h

e could see it, but when he opened his eyes, he saw nothing but grey. The two men packed their things, and Dane followed Asa deeper under the mountain’s shadow. Naked waves of stone heaved out of the clouds. They clipped on their crampons and climbed steep slashes of snow poxed with stones spat from the cliffs above. Hail hissed against the stone and swarmed around their boots.

Dane no longer felt like a zombie, but the wide-awake world was an uneasy place. He was sprinting toward a killer peak with a stranger, some kind of northern goblin who lived on the tundra with his rock and his tools, luring climbers to his mountain. The mountain had gotten into Leo’s head, the man who understood more about high places than anyone Dane knew. It had called Leo back, when Leo could have been climbing anywhere in the world. And then it kept him for good.

“What do you do in between?” Dane asked Asa. “Just wait for other climbers to fall out of the sky?”

“They come,” Asa said. “Can’t help themselves.”

Vertical steps of ice pushed through the snow. Asa took out both tools, made no mention of the rope. The hail slowed, but clouds squeezed in and blinded Dane. Asa was a dark shadow above and right, knocking loose a contrail of falling ice. Dane could see nothing but angry grey air below his feet. He had the impression the clouds were deep. The ice they kicked free seemed to accelerate unnaturally, as if sucked away into the storm.

Asa led them up a narrow ribbon of rime, ice, and snow, all Frankensteined together. The man was clearly a lunatic. Dane followed, internal alarms jangling his brainpan and tinting his vision. The snow was unreformed powder—it could barely support its own weight, let alone Dane’s. Dane reached high and snapped off a big swing, trying to cut through the outer layer and find a solid stick somewhere below. His tool rebounded off rock. His second axe, the only thing keeping Dane from spinning off into the clouds, crunched lower in sugar-crystal ice. Dane felt sick, shaky. He locked off again, cleared away the rotten powder, dry-tooled the cracked black stone below it. Intrusions of rotten ice wormed into the rock. It had happened again: he was hacking and scraping at a mountain for his life. You should quit climbing, Dane told himself. Go into grave digging.

Dane caught up with Asa on top of a broken buttress slashed with ledges. Hail spiraled around them. Rock cased in a withered old skin of ice leaned out over their heads and disappeared up through the weather.

“Rope!” Dane yelled into the wind.

Asa hooted. “You—you’re a psycho, man. I started thinking you’d never call it. I thought you were going to get us both killed.”

For one brief instant between slaps of wind, Dane imagined throwing Asa off the buttress. He could do it now, before the rope bound them together, then retreat. Just hook the hood of Asa’s shell and yank hard. Dane would dagger something evil out of the world, the man if not the mountain—and Leo would be avenged, an eye for an eye, ancient scales creaking into balance.

This small fantasy, sweet in its moment, dispersed fast. Dane didn’t feel murderous. Instead, he was flying unexpectedly high. Asa was a snake, but the truth was, Dane liked the way the man hissed and showed his teeth. Already, the sick desperation of the pitch below was fading, replaced by a rising sureness that this was the way to climb a killer mountain: mad, scared, running for your life. No margin for error, since that was just illusion anyway. Stripped of all pretenses, he and Asa could spur each other along mercilessly.

Asa already had on his harness, their absurd miniskirt of gear racked around his waist. Four screws, five pitons, a few nuts, a two-thirds set of cams. The pieces had been Asa’s choices, since he knew the mountain. Dane reached out, unclipped one of the pitons from Asa’s harness, made sure Asa was watching him, and flipped it over his shoulder.

“Seemed like the rack was heavy,” Dane said.

Asa watched the pin fall. Then Asa unclipped a second piton from his harness, held it out, and let it loose.

Dane savored, for a wind-blasted moment, just how goddamned stupid this was, each dropped piton slicing through tendons of rationality. Dane shrugged and reached for a third.

Asa clapped one hand to his waist, blocking Dane’s. He drilled Dane with a searchlight glare, then his face broke open, split by the first real pleasure Dane had seen on the man. “Crazy fuck!” Asa barked. “Where’d you come from? You win. Your lead.”

Dane took the gear from Asa and tied the ends of the ropes through his harness. He’d gotten what he’d wanted. He’d put a crack in Asa’s shell and cut himself loose of reason. Dane climbed off the ledge into the falling hail. The wind flapped past him. He felt like some huge dark bird sailing the storm. Hail popcorned off the wall, hitting his hood, the rock, his face. He pounded one of their remaining pins behind a loose tombstone, glued to the mountain by ice or vampire bat shit or god knows what, then torqued the picks of his axes into the joints of the stone, feeling the rock creak and grind. Dane growled at it, and the stone growled back.

Asa dropped away below. The hail turned to snow that flocked and wheeled midair. Dane followed a smear of thin, hard ice that he chipped and hooked. He was balanced on the tips of his monopoints, two steel toenails holding his meat to the mountain. He imagined falling and his body blatting out air like a popped balloon. Dane chipped out another quarter-inch edge and gained a foot at the cost of one more ounce of sanity. Over-gripping his tools, he squeezed and squeezed, as if holding on tighter would enlarge the scum of ice keeping him from winging off. Acid smoked out of his muscles. He was dissolving in his own juices.

Asa disappeared under the snowfall. A spike of rock stabbed out of the wall over Dane’s head. Dane half lunged, half fell, hooking one tool around it, then the second. He swung his feet up onto a stance. Something gave way inside him, more collapse than relief. Dane wrapped a sling around the finger of rock, clipped himself in, and yelled down into the blizzard telling Asa to climb.

Dane had hoped the trick he’d played with the pins would make the climbing easy. Believing in his own invincibility, he’d turn the mountain to butter and cut his way up it like a hero. Instead, fear slithered through him like dysentery, and he wondered if the heroes of old also felt a constant pressure to crap their psycho-spiritual armor and that part just didn’t make it into the songs.

Asa emerged below Dane, looking like a gargoyle crusted over with snow. His face, Dane realized, would have been the last Leo saw. Leo, who should rightfully have been ushered out by friends and disciples, had instead been with a troll who matched his mountain the way some people echo their pets. Dane kept trying to put Leo into this place, but Leo wouldn’t come, staying in the sun, on an arête of porcelain snow, baring a gleaming sliver of teeth below mirrored glacier glasses. Feeling shaggy as a goat, Dane tried to shake the ice out of his beard.

Asa passed through Dane’s stance and scratched his way up more brittle rock and cellophane ice. Twenty feet out, he’d still found no gear, and Dane willed Asa not to fall and spit himself on the spike at the belay, where he’d bleed out in Dane’s lap, an image that somehow seemed more real than the reality of Asa holding on and slowly dematerializing into the snow. A hundred feet ago, Dane had watched his own hand throw Asa off the mountain, but now the knots had been tied, and Dane silently urged Asa higher.

The climbing was like living on the edge of an exploding bomb. Shrapnel came on the wind; ice and snow flew through the air. They swung leads, and Dane felt shattered after every pitch. At one belay, a powder avalanche swept over Dane, dragging along a hundred little fists of rock. Dane remembered the hard scales Asa had sewn to his gloves. It was all dirty tricks, a mountain made for poisoned minds.

One verse of the perpetual storm ended, and blue sky yawned open. The mountain stretched out in both directions, while Dane dangled from a sling attached to a peeling scab of rock and waited for Asa to finish getting mauled by an off-width crack greased with ice. Dane had expected to be relieved if the wind ever stopped blowing out his eardrums and rattling chunks of the mountain off his helmet. Instead he half missed the way the

storm wrapped around him, kept him from seeing into the abyss. Looking up was worse because the mountain stared back. Under the suddenly eyes-wide sky, Dane felt like a rat out in the open with nowhere to hide from Ozdon’s beak and talons.

Dane followed Asa’s lead. The next anchor was a bottoming nut and tied-off knife blade, equalized in grooves inside the crack Asa had climbed. Asa was half wedged himself, trying to keep his weight off the gear.

“You should have told me not to fall,” Dane said.

“Might as well tell someone not to think about an elephant,” Asa muttered, not looking at Dane.

Dane dry-tooled up next to Asa, feeling suddenly overcautious, painfully aware that a slip would probably strip them both off. Asa was right: it was better not to know they had two bad pieces and a body wedge holding them to the mountain. Asa seemed grey and grave. Reticent. Like he’d put on years.

“You look like you’ve seen a ghost,” Dane said, hanging from his tools, forcing a laugh.

“Get on with it,” Asa grumbled, shifting his knee lock inside the crack. “Sick bastard. Climbing with you is like a ticket to the creep show.”

Coming from Asa, that seemed farfetched, but Dane preferred being under the man’s skin to in his crosshairs, so he didn’t bother saying right back at you. Dane took their hardware one-handed. The crack above widened to a bottomless groove slicing into the mountain, and the angle dropped down off vertical. The rock whispered and flexed under Dane’s crampon points. A millimeter of ice glazed the hollow stone. Outside the groove, giant stone teeth twisted up out of a pair of jawbone ridges. They looked grotesquely unstable, with no earthly reason Dane could see for them to stay upright.

Twenty feet. Fifty feet. No gear. The rope trailed below Dane uninterrupted. Dane scraped and pressed against the shifty rock, bridging the groove, one foot on either side. Each hold was a time bomb. Dane’s blood ticked off the seconds. Eighty feet. Dane nodded his head to the beat of his pulse. A hundred feet. It didn’t matter. He knew the rock better than himself, knew just which holds to use and how to use them. He couldn’t be shook loose.

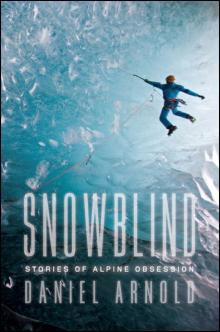

Snowblind

Snowblind