- Home

- Daniel Arnold

Snowblind Page 2

Snowblind Read online

Page 2

Her husband cut her off. “For Christ’s sake, Angie, it’s the kid’s partner. Can’t you wait a day?” He turned to me and said, more softly, “Horrible, horrible. He’ll have a good slideshow. I’d have put up my ten bucks. The Tragedy of Rex. Killable, as are we all. He got what he deserved. I wonder if anyone will miss him. You just down off the mountain?”

I told him I was, while his wife muttered to herself that booty was booty.

“How’d it go?”

“Miserable,” I said. “Same storm as the kid said. Had me shitting into bags in my tent for days. Couldn’t go outside. Would’ve ended up with a frostbite enema.”

“You on your own?” he asked.

“I was going to solo the Slovene Route, but I never even got started.”

“Yeah? Sounds like you should have teamed up with the kid. He didn’t stay in his tent five days.”

“Fuck off.”

I kept my eyes on JD, waiting, thinking that someone probably would miss Rex. Most everyone’s got someone. JD had a gulp of wine, put it back on the table. Two Americans who looked city-soft by contrast sat down to his right and left, and he couldn’t look at them, didn’t know where to put his eyes. They spoke quietly, faces milky-kind. Comforting words, sure. One put a hand on JD’s shoulder. Hell, they all missed Rex now that he was dead.

“Kid must have some of the beast in him to have survived all that,” I said. “He could make it up some serious routes someday.”

My friend shrugged and sucked on the dregs of his maté. “Sure, but what’ll his head be like after this? Sounds like he wouldn’t know a fool if one up and died on him. Why should a mountain give a fool an hour?” Pleased with himself, he hiccoughed through his tea. “A fool and his hour are soon parted!” he said.

One of the Germans detached himself from the other three and walked over to the table at the center of the room. He pushed his face right into JD’s and said, “You didn’t put the sleeping bag on your partner?” His voice was thick, like he was talking through brown stout. “No hot drink? No help? You should not go back into the mountains.”

Before JD had a chance to react, the man who’d put his hand on JD’s shoulder leapt up and planted the same hand on the German’s chest and gave a little shove. The German looked shocked, then shook his head and stalked off.

Angela’s husband slurped his tea dregs again and spat brown leaves back into his gourd, then said: “Trust the Germans to get right to the point!” He giggled—a high sound like a dying fan belt.

But I was watching JD. I watched him watch the German get pushed back. His shoulders went up, his head tilted back, he had a sip of wine. Something unbent inside him. I wondered if anyone else even noticed.

THERE WAS A party that night, a typical climber shindig. Someone’s always ready to celebrate, and others have sorrows, alpine or otherwise, and at least one group of smooth, clean faces will be looking to medicate their nerves. Two Brits who had summitted via the normal route before the storm brought three cases of Andino, the local brew that came in brown liter bottles with little red-and-silver labels. Miscellaneous liquors emerged from pockets and brown bags, and Paco made available two bottles of wine with his stock benediction, “for the summertime.”

All through the afternoon, JD’s story continued to bother me. Maybe I thought I could have told it better, that it was wasted on him. I could find the soul of it. I wanted a go at it. While I slipped back into the comforts and claustrophobias of the house, I kept seeing the way he’d straightened up and lifted his eyes. I felt hunched by comparison.

We spilled out onto the roof at twilight, into the first pleasant temperatures for me in three weeks. On the mountain, I’d gone from heat itch to frostbite so fast my body still had complaints about the one as it warned of the other. Now I’d showered and shaved away most of my beard, which killed two razors plus most of the sharpness of a third. In the end, I had to leave a thick under-mane of coiled fur below my jaw and chin because I’d only thought to buy two razors and couldn’t scrounge more than one other at the house. But my face, at least, felt light and airy. The roof was bordered on three sides by a low wall and finished with cream-colored tiles that were cracked and dusty. My tent was shoved to one corner, and from the look of things, it would be hours before the rooftop was mine.

It was nine o’clock, but down on the streets, the night had just begun, and the first evening walkers headed out for early dinner, or to enter the discotheques before a cover was charged. Strings of bare lightbulbs nailed tree-to-tree through the park blocks across from Calle 25 de Mayo swung back and forth on the whim of the breeze, and kids who were too young for the clubs shadowboxed dance steps in and out of the moving lights to the rhythm of the music leaking into the streets.

Paco had an old steel-housed cassette deck, and he rolled the whole system out onto the roof and perched the two speakers on opposite walls. As usual, there was a shortage of women, and Angela had an unlimited number of partners waiting to attempt a tango to her standards. Meantime I talked to her husband, each of us working on a giant Andino.

“It’s no wonder so few Mendozans climb the mountain,” he said. “Look at the women. Have you ever seen perfection like that? They walk around in their little skintight shirts and pants, with breasts like—god—I didn’t even know breasts were supposed to look like that before I came here. I’d be afraid to touch them. I’d want a debriefing from the museum curator first, you know? You don’t get climbers in paradise, man.”

The Czechs sat at a square table and played cards with a Swiss trekker. They passed a communal bottle of scotch counterclockwise and periodically broke into a few lines of song based on a pattern I couldn’t follow. JD had a seat along the wall looking out over the park. He hadn’t shaved, and from the way his beard glistened in the half-light, it seemed unlikely he’d washed yet either. The two Brits sat next to him, squawking like a couple of birds.

The Brits were so damned happy they made me jumpy. They’d climbed their way into paradise and were making the most of it. Say what you like about beauty and brotherhood, the real reason to go up a mountain is to pile on as much tension and fear and desire as can be borne so that the other side is a blissful place to float in for a few days. That’s where the Brits were. JD must have half tasted it sitting there next to them. I could have been there, too. And when you’re barred at the gates, outside looking up, you get irritable—the alpinist’s version of blue balls, withdrawal. There couldn’t have been a pair of eyes on that rooftop that didn’t look over at the Brits with envy, because the best part about going climbing is to be finished with the climb.

“You ever heard of someone dropping over dead in the snow?” I asked my friend. “I mean, walking one minute and then dead the next?”

“No.” He shrugged. “But come on, what was he supposed to do, throw his partner over one shoulder and hike him up the mountain? He’s not Alex Lowe.”

I poked my finger into his chest. “Sure. But that’s not what he said.”

I finished my beer and pulled two more from the last of the three cases and took them over to JD. I opened one for myself and offered one to him, but he waved me off.

“Not for me,” he said. “I don’t need it. It feels good just to breathe.” He had his back to the party, his feet up on the wall.

“Did you ever check his pulse?” I asked.

“What?”

“Rex. Did you ever check his pulse? I know you’ve thought about it since.”

The Brits hastily pulled each other up out of their chairs. “Best to leave them,” I heard one say. “No need for another international incident.” They swung each other onto the dance floor, making mincing steps around Angela and her latest suitor.

“Get out of my face,” JD said.

“Look, it’s all part of the process.” I took one of the Brits’ chairs and slid it over so that we were sitting face-to-face. “Don’t just abandon your partner up there.”

“I didn’t kill Rex!” he

said. “It was the fucking storm. Are you crazy? We needed one more hour. That’s all.”

“Wasn’t the storm that killed Rex,” I said. “Rex killed himself. Sounds like you about killed yourself, too. The question is, did you take his pulse?”

“No.”

“See, that wasn’t so hard. Better, too, isn’t it?”

“Fuck you.” The black patch of frostbite on his nose made it look like he had a hole in his face. “I couldn’t take my hands out of my gloves. I was barely standing. I checked. He was dead.”

“How can you know that for sure? That’s the thing. Alive or dead, you had to leave him. But you don’t know which, and it’s better to know that. We’re talking about the future here. We’re talking about healing.”

“I’m not thinking past tonight.”

Somehow I had become sidetracked. I worked to clear my head, to start over. I had lost the direction I wanted to take our talk. I tried to wrestle it back toward my original intention.

“You know what the two of us should do?” I said. “We should go back up and find Rex and build him a cairn. We’ll take an extra bottle of white gas and dump the whole thing out and have a big fire. You don’t want to leave him like that, just slumped over in the snow. You and I. We’ve got to give him a proper send-off.

“Give yourself a few days to rest and heal, then we’ll do it. It’ll be good. Get right back up there. The real mountain doesn’t give a damn, but the mountain in your mind,” I said, tapping his forehead with one finger, “will only get bigger if you let Rex fester and rot.”

Then JD did something I did not see coming. I was sitting there, leaned back in my chair, with my back to that low wall that separated the roof from the street. He reached forward and grabbed my throat with one hand and pushed. He was remarkably strong—his fingers felt like stone around my neck. He pushed until my chair was tipped back over the wall and I was balanced with my top half hung out into space and my bottom half ready to come tumbling after and JD holding onto me by the neck.

“This is all climbing is,” he said. “Fear before the fall. Waiting to see whether the mountain is going to drop you or not. See, we can do it right here. What do you think? Is it going to cut you loose? Are you gonna die?”

I heard approaching feet, excited voices. I stared straight back into JD’s eyes, which were hard and cold and made me think of old ice that hasn’t seen the sun in years. I waited for the tension in his fingers to change for better or worse. He squeezed and pulled me back from the edge and dumped me down on the rooftop.

“There, we’ve climbed the mountain, asshole,” JD said.

Hands reached out and led JD away. Someone righted my chair, but he walked away too, and I was left alone by the wall. That was it for the party for me. I sat on one edge, by my tent, staring out at the hustle of the nighttime city, rubbing my bruises through my throat-fur. Eventually the others all stumbled down to their rooms, and I was the only one.

Paco’s brother came by with a broom and a trash bag. He put a hand on my shoulder. “A hard night. Happens sometimes. The liquor—it goes quickly to your head when you come down from the mountain.”

I looked up, and his face seemed ancient, but his eyes were young, and his whole demeanor seemed placid and brotherly, and I couldn’t imagine he’d felt a day’s turmoil in his life. “It’s been hard for years,” I said. “It’s always been hard.”

SIX YEARS PASSED before I saw JD again. I married a nurse who worked at the Yosemite clinic, and I found a spot on the search-and-rescue team for myself. We had a little cabin that came with a refrigerator and telephone service and an electric fan on the ceiling and a wood-burning stove. We had big trees in our yard and listened to the sound of the waterfall at night.

On an Indian summer day in October, a tabletop-sized flake cut loose on Zenyatta Mondatta, on the east side of El Cap, shredding the leader’s rope, and I was on body-part recovery. I hiked up along the base toward the scene and paused on the way to talk to a climber who was sitting at the base of the North America Wall, in the middle of a pile of gear, smoking a joint.

“Going up?” I asked.

“No man, I had to bail out.”

“You on your own?”

“I was going to solo Sea of Dreams, but I never really got started. I’ve got an old rotator cuff tear, right here,” he said, stretching his arm above his head. “I could feel it, you know, getting bad. I figured the last thing I want is for it to go out on me up there.”

He was filthy from neglect and fat around the edges. His hair was stringy, not in intentional dreads but ratty tangles. His eyes were bloodshot, and the skin around their sockets, and covering his neck, was thick and fleshy. His collars and hems were all stretched out. I might not have recognized him but for his beard, which was blond and curly and triggered memories of a rooftop shouting match in what seemed to be a past life.

The strange thing was, I couldn’t be sure which oily blond beard I saw—his or mine. His present self, seated alone on the rock below the climb he’d never really started, looked more like the man upended over the Mendoza streets than the young man he’d been. And I thought: Did we do this to you? And I thought: Good lord, boy, be careful who you tell your stories to. Whatever you do, don’t tell them to us. You might as well ask mercy of vultures. But maybe he should never have offered himself or his partner in the first place.

So I said, “That’s the way it goes sometimes,” and I cursed myself for having nothing else to say to him.

“Heard someone got the chop,” he said. “You part of the cleaning crew?”

“Yes.”

“Have you gotten his partner down yet?”

“He rapped down on his haul line and what was left of the lead line. We’re putting him up in the SAR cabins for a few days while he gets his head together. There’s always someone there who’s off shift to keep him company.”

JD stretched his lips into the shape of a grin. “You ought to have him up here on recovery,” he said. “That’d help him figure himself out.” He laughed, a harsh wheeze. “I had a partner die once. It’s healthy to see at least one body in your life. Reminds you what it’s all about, where the lines are drawn. We ought to celebrate that man’s passing!” And he danced, a clumsy little shuffle in the midst of his tattered pile of gear, waving that acrid joint above his head.

DEAD TILL PROVEN OTHERWISE

TWO AM. ANN chokes off the alarm on her watch. Her bones ache, even the sockets of her eyes. She probes her flesh, groping for her moxie. How much does she have left? Yeah, and how much will she need? Half breaths of wind rattle the fabric of her bivy sack. Ha! One vertical mile of snowy Alaskan beast below the foot-wide sleeping ledge she’s chopped in the ice, and the beast is snoring. Ann unzips the hood of her bivy sack. Stars! Bright goddamn stars. And cold. Cold as a wage slave’s soul. Perfect. Day three, and her weather window has held. She’ll meet the sun on top of the mountain.

She pops two caffeine pills and swallows a gel. She puts her earphones in and thumbs up the sound. Tom Paine lunges at her ears like a dog barking nose-down in a hole: Nothing more certain than death / Nothing less sure than its time. White noise obliterates the last syllable, turns to nasty, fire-breathing music just when she’s sure her eardrums will tear. Ann made this mix expressly for the small hours. The hairs prickle off her arms. Guitars peeling back her skin, that’s what she wants. Metal and caffeine, the gods’ own breakfast. All else is just calories. Inside her bag, Ann wrestles her plastic doubles onto her feet. Paine comes back to remind her that men beg for kings to rule them. No, she’ll have no kings.

Ann unzips her cocoon, clips herself in short to the two ice screws keeping her leashed against gravity. She packs away her sleeping kit. Her headlamp pricks the darkness, barely wounding it. The horns of the mountain above and the mind-trapping drop below are shadows on black shadows. She steps into her crampons, her favorite part of the morning. With spikes on her feet, she can go crusading.

The cold

already has its teeth in her, and she’s no apple-cheeked gal. When single digits slap her in the face, the color dies out of her skin, and Ann knows she must be chalk white. She grins juicily. She should have brought some props, some plastic fangs and black eyeliner, give the mountain a scare. Deep night, laser-white stars, the gigantic black void behind and below—Ann imagines climbing into outer space. Drum blasts displace her skull bones. Heat rises through her flesh to meet the cold. The music is her armor against the void. She means someday to write out her will, which will consist of nothing but a playlist for her funeral, and that will make her happy. Ann threads the leg loops of her harness, drinks half her water, and puts her pack on her back. Her insides twitch. She feels vicious. The knife cutting open the future. She doesn’t know what she’ll find there, but it’s bound to be different from the past if she can just make herself sharp enough.

Fuck the climbing press and their backhanded praise, the “Psycho Bitch Rises” headline most of all. She was told to relax and take it as a compliment. Fuck ’em. Does she look relaxed?

Fuck the city people hiding from death in their homes. Binding themselves to their neighbors and their neighbors’ neighbors till they’re left wriggling on their own webs. Secure, sure. Ann’s fighting the good fight, trying to bump humanity off its inward spiral.

Fuck the whole brotherhood of the rope—they’re just as bad. Dudes tied together, married by their knots and common purpose. Greybeards in Anchorage or Aspen or wherever they take themselves to rot in their own memories and dream up new certifications and associations. One way or the other, head up or down, she’ll be there to remind them of their white hair and their caution.

Ann cups her mouth with her gloves and owl-screeches at the night, then takes a breath and cycles a few more times through her mantra: DPO. Dead till Proven Otherwise. She has the words tattooed in black under her collarbones. From the moment she touches the mountain, she is dead, clawing at the dirt from six feet under. She swings her right-hand tool into the ice and cleans the anchor screws with her left. If she wants to live, she’ll have to prove it.

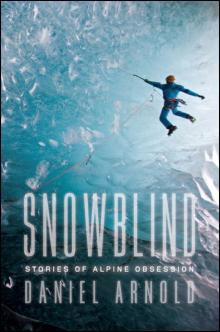

Snowblind

Snowblind